In the early 70s of the XIX century. Russian revolutionaries stood at a crossroads.

Spontaneous peasant uprisings that broke out in many provinces in response to the reform of 1861 were suppressed by the police and troops. The revolutionaries failed to carry out the plan of the general peasant uprising planned for 1863. NG Chernyshevsky (see art. "Contemporary". NG Chernyshevsky and NA Dobrolyubov) languished in hard labor; his closest associates who made up the center revolutionary organization, were arrested, some died or also ended up in hard labor. In 1867 A. I. Herzen's "The Bell" fell silent.

In this difficult time, the young generation of revolutionaries was looking for new forms of struggle against tsarism, new ways to wake up the people, to win them over to their side. The young people decided to go “to the people” and, together with education, spread the ideas of revolution among the dark, downtrodden peasantry and lack of rights. Hence the name of these revolutionaries - populists.

In the spring and summer of 1874, young people, most often students, commoners or noblemen, hastily mastered this or that profession useful to the peasants and dressed in peasant dress, “went to the people”. Here is how a contemporary tells about the mood that gripped the advanced youth: “Go, no matter what, go, but be sure to wear an army jacket, a sundress, simple boots, even sandals ... Some dreamed of a revolution, others just wanted to see, - and spread throughout Russia as artisans, peddlers, hired for field work; it was assumed that the revolution would take place no later than in three years - this was the opinion of many. "

From St. Petersburg and Moscow, where at that time there were most of the student youth, the revolutionaries moved to the Volga. There, in their opinion, the memories of the peasant uprisings led by Razin and Pugachev were still alive among the people. A smaller part went to the Ukraine, to the Kiev, Podolsk and Yekaterinoslav provinces. Many went to their homeland or to places where they had any connections.

Dedicating their lives to the people, striving to become closer to them, the Narodniks wanted to live their lives. They ate extremely poorly, sometimes slept on bare planks, limited their needs to the bare essentials. “We had a question,” wrote one of the participants in the “walk to the people”, “is it permissible for us, who took the wanderer's staff in our hands ... to eat herrings ?! For sleeping, I bought myself a matting, which was already in use, at the bazaar, and put it on the plank bunks.

The dilapidated washcloth was soon rubbed through, and I had to sleep on bare boards. " One of the outstanding populists of that time, P.I. It trained populists who wanted to go to the village as shoemakers, and kept forbidden literature, stamps, passports - everything necessary for the illegal work of revolutionaries. Voinaralsky organized a network of shops and inns in the Volga region, which served as strongholds for the revolutionaries.

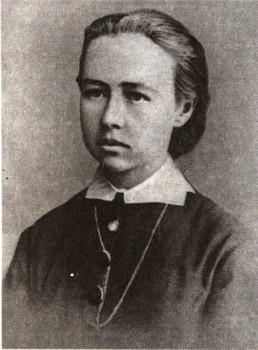

Vera Figner. Photo of the 1870s.

One of the most heroic women revolutionaries, Sofya Perovskaya, after graduating from the courses of rural teachers, in 1872 went to the Samara province, to the village of the landowners Turgenevs. Here she took up inoculating smallpox to the peasants. At the same time, she got to know their lives. Having moved to the village of Edimnovo, Tver province, Perovskaya entered the teacher's assistant folk school; here she also treated the peasants and tried to explain to them the reasons for the plight of the people.

Dmitry Rogachev. Photo of the 1870s.

Another remarkable revolutionary, Vera Figner, draws a vivid picture of work in the countryside, though dating back to a later time. Together with her sister Eugenia in the spring of 1878, she arrived in the village of Vyazmino, Saratov province. The sisters began by organizing an outpatient clinic. The peasants, who had never seen not only medical care, but also a human attitude towards themselves, literally besieged them. For a month Vera received 800 patients. Then the sisters managed to open a school. Yevgenia told the peasants that she was undertaking to teach their children free of charge, and she had 29 girls and boys. Pi in Vyazmino, nor in the surrounding villages and villages there were no schools at that time. Some of the students were brought in twenty miles away. Adult men also came to learn to read and write, especially arithmetic. Soon Evgenia Figner was called by the peasants nothing more than "our golden teacher."

After graduating from the pharmacy and school, the sisters took books and went to one of the peasants. In the house where they spent the evenings, the relatives and neighbors of the owners gathered and listened to the reading until late in the evening. We read Lermontov, Nekrasov, Saltykov-Shchedrin and other writers. There was often talk about the hard peasant life, about the land, about the attitude towards the landowner and the authorities. Why did hundreds of young men and women go exactly to the village, to the peasants?

The revolutionaries of those years saw the people only in the peasantry. The worker in their eyes was the same peasant, only temporarily torn from the land. The Narodniks were convinced that peasant Russia could bypass the capitalist path of development that was painful for the people.

Arrest of a propagandist. Painting by I. Repin.

The rural community seemed to them to be the basis for the establishment of a just social system. They hoped to use it for the transition to socialism, bypassing capitalism.

The Narodniks carried on revolutionary propaganda in 37 provinces. The Minister of Justice wrote at the end of 1874 that they had managed to "cover, as it were, a network of revolutionary circles and individual agents over half of Russia."

Some Narodniks went “to the people”, hoping to quickly organize the peasants and rouse them to insurrection, others dreamed of launching propaganda with the aim of gradually preparing for the revolution, and still others only wanted to educate the peasants. But they all believed that the peasant was ready to rise to the revolution. Examples of past uprisings led by Bolotnikov, Razin and Pugachev, the scale of the peasant struggle during the period of the abolition of serfdom supported this belief in the populists.

How did the peasants meet the Narodniks? Have these revolutionaries found a common language with the people? Did they manage to rouse the peasants to the uprising, or at least prepare them for this? No. Hopes to rouse the peasants for revolution did not materialize. The participants in the “going to the people” only succeeded in treating the peasants and teaching them to read and write.

Sofia Perovskaya

The Narodniks imagined an "ideal peasant", ready to abandon the land, home, family and take an ax at their first call to attack the landlords and the tsar, but in reality they faced a dark, downtrodden and infinitely oppressed man. The peasant believed that the whole burden of his life came from the landowner, but not from the tsar. He believed that the king was his father and protector. The peasant was ready to talk about the severity of taxes, but it was then impossible to talk with him about the overthrow of the tsar and about the social revolution in Russia.

The brilliant propagandist Dmitry Rogachev traveled to half of Russia. Possessing great physical strength, he pulled a strap with barge haulers on the Volga. Everywhere he tried to carry on propaganda, but could not captivate any peasant with his ideas.

By the end of 1874, the government had arrested over a thousand populists. Many were deported without trial to remote provinces under police supervision. Others were imprisoned.

On October 18, 1877, in the Special Presence of the Senate (the highest judicial body), the "case of revolutionary propaganda in the empire" began to be heard, which was called the "trial of the 193s" in history. One of the most prominent populist revolutionaries, Ippolit Myshkin, delivered a brilliant speech at the trial. He openly called for a universal popular uprising and said that the revolution can be accomplished only by the people themselves.

Realizing the futility of propaganda in the countryside, the revolutionaries switched to other methods of fighting tsarism, although some of them also tried to get closer to the peasantry. The majority went on to direct political struggle against the autocracy for democratic freedoms. One of the main means of this struggle was terror - the murder of individual representatives of the tsarist government and the tsar himself.

The tactics of individual terror hindered the awakening of the broad masses of the people to the revolutionary struggle. In place of the murdered tsar or dignitary a new one rose, and even more severe repressions fell upon the revolutionaries (see article "March 1, 1881"). Performing heroic deeds, the Narodniks were never able to find a way to the people in whose name they gave their lives. This is the tragedy of revolutionary populism. Nevertheless, the populism of the 70s played an important role in the development of the Russian revolutionary movement. Lenin highly valued the Narodnik revolutionaries for trying to awaken the masses to a conscious revolutionary struggle, calling on the people to revolt, to overthrow the autocracy.

“Going to the people” is a phenomenon that has no analogues in any country in the world. Agrarian Russia was not shaken bourgeois revolutions... They rose against autocracy and serfdom the best representatives nobility. The peasants received freedom under the reform of 1861, which was of a half-hearted nature, which caused their dissatisfaction. The raznochintsy, who believed in the possibility of achieving socialism through a peasant uprising, took over the revolutionary baton. The article is devoted to the movement of the progressive intelligentsia for education and revolutionary propaganda among the people.

Background

Young people from the middle class were drawn to education, but the fall of 1861 saw an increase in tuition fees. Mutual aid funds that help poor students were also banned. Unrest began, brutally suppressed by the authorities. Activists were not only expelled from universities, but also thrown out of life, since they were not hired for public service. called the victims "outcasts of science." In the Kolokol magazine published abroad, he invited them to go “to the people”.

So spontaneously began "going to the people." This movement grew into a mass movement in the early 70s, acquiring a special scope in the summer of 1874. The appeal was supported by the revolutionary theoretician P.L. Lavrov. In his "Historical Letters" he expressed the idea of the need to "pay the debt to the people."

Ideological inspirers

By that time, a utopian idea was formed in Russia about the possibility of a peasant revolution, the victory of which would lead to socialism. Its adherents were called populists, because they talked about a special way of the country's development, idealizing the peasant community. The reasons for "going to the people" lie in the unconditional belief of the commoners in the correctness of this theory. Three currents emerged in revolutionary ideology (the diagram is presented just above).

The anarchist believed that a call to rebellion was enough for the peasants to take up the pitchfork. PL Lavrov suggested that the "critically-minded" representatives of the intelligentsia first help the people (peasants) realize their mission, in order to then jointly create history. Only P. N. Tkachev argued that the revolution should be carried out by professional revolutionaries for the people, but without their participation.

The "march of the people" of the populists began under the ideological leadership of Bakunin and Lavrov, when the first associations were already created - the Moscow and St. Petersburg circles of N. V. Tchaikovsky and the "Kiev Commune".

Basic goals

Thousands of propagandists went to remote villages disguised as merchants and artisans disguised as artisans. They believed that their costumes would inspire the confidence of the peasants. They carried books and propaganda proclamations with them. Thirty-seven provinces were covered by the movement, especially Saratov, Kiev and Upper Volga. The triune goal of "going to the people" included the following points:

- Study of peasant sentiments.

- Promotion of socialist ideas.

- The organization of the uprising.

The first stage (until the middle of 1874) is called "flying propaganda", because the revolutionaries, relying on their strong legs, moved from one settlement to another, without staying long. In the second half of the 70s, the second stage began - "sedentary propaganda". Narodniks settled in villages, acting as doctors, teachers or artisans, specially mastering the necessary skills.

results

Instead of supporting the revolutionaries, it was met with distrust. Even in the Lower Volga region, where the traditions of Emelyan Pugachev and Stepan Razin should be alive. The peasants eagerly listened to speeches about the need to divide the landlord's land and abolish taxes, but as soon as it came to calls for rebellion, interest faded. The only real attempt at an uprising was the "Chigirinsky conspiracy" of 1877, brutally suppressed by the autocracy. Often the villagers themselves handed over the propagandists to the gendarmerie. For six years, 2,564 people were involved in the inquiry.

The painting by I. Repin in 1880 captures the moment of the arrest of a propagandist in a peasant hut. The main piece of evidence is a suitcase with literature. The picture clearly shows how the “going to the people” ended. This led to massive repression. The most active were convicted in St. Petersburg in 1878. The trial went down in history as the "Trial of one hundred and ninety-three", in which about a hundred people were sentenced to exile and hard labor.

Historical meaning

Why did the revolutionary youth movement end in failure? Among the main reasons are:

- The unpreparedness of the peasantry for a revolutionary coup.

- Lack of connections and general leadership.

- Police ferocity.

- Lack of conspiracy skills among propagandists.

To what conclusion did the unsuccessful “going to the people” lead? This can be understood from the following historical events... A massive departure from Bakunism and the search for new forms of political struggle began. The need arose for a unified all-Russian organization on the terms of the strictest secrecy. It will be created in 1876 and in 2 years will go down in history under the name "Land and Freedom".

going to the people

mass movement of youth to the countryside. Began in the spring of 1873, the largest scale - spring - summer 1874. Objectives: the study of the people, the promotion of socialist ideas, the organization of peasant uprisings. Centers: St. Petersburg and Moscow circles "Tchaikovsky", "Kiev Commune". It covered 37 lips. European Russia... By November 1874 St. 4 thousand people, the most active participants were convicted in the "193 trial".

Going to the people

"Going to the people" mass movement of democratic youth in the countryside in Russia in the 1870s. For the first time, the slogan "To the people!" put forward by AI Herzen in connection with the student unrest of 1861 (see "The Bell", fol. 110). In the 1860s - early 1870s. Attempts to get closer to the people and revolutionary propaganda in their midst were made by members of the "Land and Freedom", the Ishutinsky circle, the "Ruble Society", and Dolgushinites. A leading role in the ideological preparation of the movement was played by PL Lavrov's Historical Letters (1870), which called on the intelligentsia to “pay the debt to the people,” and The Position of the Working Class in Russia by V. V. Bervi (N. Flerovsky). Preparing for the mass "H. in n. " began in the fall of 1873: the formation of circles, among which the main role belonged to the Tchaikovites, was intensified, the publication of propaganda literature was established (the printing houses of the Tchaikovites in Switzerland, I.N. Began in the spring of 1874, the mass "H. in n. " was a spontaneous phenomenon that did not have a single plan, program, organization. Among the participants were both supporters of P.L. Lavrov, who advocated the gradual preparation of the peasant revolution through socialist propaganda, and supporters of M.A. Bakunin, who strove for an immediate revolt. The democratic intelligentsia also took part in the movement, trying to get closer to the people and serve them with their knowledge. Practical activities"Among the people" erased the differences between directions, in fact, all the participants carried out "flying propaganda" of socialism, roaming the villages. The only attempt to raise a peasant uprising was the Chigirin conspiracy (1877).

The movement that began in the central provinces of Russia (Moscow, Tver, Kaluga, Tula) soon spread to the Volga region (Yaroslavl, Samara, Nizhny Novgorod, Saratov and other provinces) and Ukraine (Kiev, Kharkov, Kherson, Chernigov provinces). According to official data, the propaganda covered 37 provinces of European Russia. The main centers were: the Potapovo estate of the Yaroslavl province (A.I. Ivanchin-Pisarev, N.A.Morozov), Penza (D.M. Rogachev), Saratov (P.I. brothers Zhebunev), "Kiev Commune" (V. K. Debogoriy-Mokrievich, E. K. Breshko-Breshkovskaya) and others. in n. " O. V. Aptekman, M. D. Muravsky, D. A. Klements, S. F. Kovalik, M. F. Frolenko, S. M. Kravchinsky and many others took an active part. By the end of 1874, most of the propagandists had been arrested, but the movement continued in 1875. In the second half of the 1870s. "NS. in n. " took the form of "settlements" organized by "Land and Freedom", "sedentary propaganda" (the arrangement of settlements "among the people") came to replace the "flying" one. From 1873 to March 1879, 2,564 people were brought to the inquiry in the case of revolutionary propaganda, the main participants in the movement were convicted in the "trial of the 193s." "NS. in n. " It was defeated primarily because it relied on the utopian idea of populism about the possibility of the victory of the peasant revolution in Russia. "NS. in n. " did not have a leading center, most of the propagandists did not possess conspiracy skills, which allowed the government to crush the movement relatively quickly. "NS. in n. " was a turning point in the history of revolutionary populism. His experience paved the way for a departure from Bakunism, accelerated the process of maturation of the idea of the need for a political struggle against the autocracy, the creation of a centralized, conspiratorial organization of revolutionaries.

Source: Process of the 193s, M., 1906: Revolutionary populism of the 70s. XIX in Sat. documents, v. 1-2, Moscow-Leningrad, 1964-65; The propaganda literature of the Russian revolutionary populists, L., 1970; Ivanchin-Pisarev A. I., Walking among the people, [M. ≈ L., 1929]; Kovalik S. F., The revolutionary movement of the seventies and the process of the 193s, M., 1928; Lavrov P.L., Narodniks-propagandists 1873-1878, 2nd ed., L., 1925.

Lit .: Bogucharsky V. Ya., Active populism of the seventies, M., 1912; BS Itenberg, Movement of revolutionary populism, M., 1965; Troitsky N.A., Big Society of Propaganda 1871-1874, Saratov, 1963; Filippov R. V., From the history of the populist movement at the first stage of "going to the people", Petrozavodsk, 1967; Ginev V.N., Narodnik movement in the Middle Volga region. 70s of the XIX century, M. ≈ L., 1966; Zakharina V.F., Voice of revolutionary Russia, M., 1971; Kraineva N.Ya., Pronina P.V., Populism in the works of Soviet researchers for 1953-1970, M., 1971.

The populists began the most important task of their activity in the 70s. saw in the involvement of the people in the revolutionary struggle. At first, this issue was considered abstractly, in the form of general declarations about revolutionary propaganda. An important role in the development of a practical view of this problem was played by the illegal magazine Vperyod! Published since 1873 under the editorship of Lavrov. On the pages of the journal, Lavrov and his supporters developed ideas about the gradual scientific preparation of the individual for revolutionary activity... But this gradualness did not satisfy the youth, who were eager for immediate action. The revolutionaries increasingly turned to Bakunism, which called for immediate rebellious activity. Among the Tchaikovites, N.A. Kropotkin, who believed that in order to carry out the revolution, the advanced intelligentsia should live a popular life, work among the people, create circles of active peasants in the villages and establish ties between such circles. Along with this, Kropotkin supported Lavrov's idea of the scientific training of the individual, the enlightenment of the masses. A doctrine took shape that combined the positions of Lavrov and Bakunism, but with the complete dominance of Bakunin's idea of denying the political struggle.

For the revolutionaries of the early 70s. "Going to the people" as a form of communication between socialist theory and the popular movement was no longer a discovery. The first attempts to "walk" belong (to the end of the 50s - the beginning of the 60s). The most famous was the propaganda activities of the author of the proclamation "Young Russia" P.G. Zaichnevsky, who made his first voyage to the village back in 1861. In the early 70s. there were also many single cases of “going to the people”. Attempts to carry out propaganda among the peasantry belonged to the prominent representatives of populism S. Perovskaya, S. Kravchinsky, D. Rogachev, and others.

By 1874, a general view was formed about the organization of mass “going to the people”. Against the background of the disunity of the populist circles and the absence of a single leading center, this common aspiration was an indicator of the consolidation and growth of the forces of the revolutionaries. The beginning of the mass “Walking to the People” dates back to the spring of 1874. The propaganda covered about forty provinces, mainly in the Volga region and southern Russia. The youth who went to the people understood their tasks in different ways: some naively believed to immediately raise the revolution and destroy landlord land ownership, others considered the main thing to popularize socialist ideas among the people, and still others set the modest tasks of educating the people and improving their current situation. The mass "going to the people" is associated with a significant social upsurge, which was drawn into revolutionary movement and casual travel companions. Thus, the movement included a very heterogeneous composition of participants.

In practice, "going to the people" looked like this: young people, one by one or in small groups under the guise of trade intermediaries, craftsmen, etc., moved from village to village, speaking at meetings, talking with peasants, trying to instill distrust of the authorities, urged not to pay taxes, disobeying the administration, explained the injustice of the distribution of land. Refuting centuries of popular belief that royal power from God, the populists tried to promote atheism. However, faced with the religiosity of the people, they began to use it, referring to the ideas of Christian equality. In search of opposition elements, the populists attached particular importance to propaganda among the Old Believers and sectarians. Most often, the populist propagandists carried proclamations and illegal literature with them.

There were cases when revolutionaries opened workshops in villages, worked as teachers, clerks, zemstvo doctors, etc., thus trying to penetrate deeper into the people and create revolutionary cells among the peasantry.

In 1875 and 1876. "Going to the people" continued. The experience of the first year showed that the peasantry did not accept socialist appeals, and therefore the Narodniks began to pay more attention to clarifying the current needs of the people. However, even in this case, the influence of propaganda on the peasants, according to the Narodniks themselves, was superficial. Attempts to rouse the people to fight did not bring serious consequences, but for the participants in the movement, the appeal to the people was of great importance, first of all, enriching them with the experience of revolutionary action.

Going to the people

Movement among Russian student youth in the 1970s. XIX century.

In those years, among the youth, interest in higher education especially to natural sciences... But in the fall of 1861, the government raised tuition fees and banned student mutual aid funds. In response to this, there were student unrest at the universities, after which many were expelled and seemed to be thrown out of life - they could neither get a job in government service (due to "unreliability"), nor study at other universities.

At this time, A. I. Herzen wrote in his magazine "Kolokol": "No. Where can you go, young men, from whom science has been locked? .. Tell you where?.: To the people! To the people! - this is your place, exiles of science ... ”Those expelled from universities became rural teachers, paramedics, etc.

In subsequent years, the number of "outcasts of science" grew, and "going to the people" became a mass phenomenon.

Usually, “going to the people” is understood as its stage, which began in 1874, when revolutionary-minded youth came to the people with a very specific goal - to “re-educate the peasant,” “revolutionize the peasant consciousness,” raise the peasant to an uprising, etc.

The ideological leaders of this "movement" were the populist N. V. Tchaikovsky (Tchaikovsky), the revolutionary conservative theoretician P. L. Lavrov, the revolutionary anarchist M. A. Bakunin, who wrote: "Go to the people, there is your field, your life, your science. Learn from the people how to serve them and how best to conduct their business. "

V modern language used ironically.

Going to the people ", mass movement of democratic youth to the countryside in Russia in the 1870s. For the first time, the slogan "To the people!" put forward by AI Herzen in connection with the student unrest of 1861 (see "The Bell", fol. 110). In the 1860s - early 1870s. attempts to get closer to the people and revolutionary propaganda among them were made by members "Land and Freedom", Ishutinsky circle, "Ruble society", Dolgushin people. The leading role in the ideological preparation of the movement was played by "Historical Letters" by P. L. Lavrova(1870), calling on the intelligentsia to "pay the debt to the people," and "The Situation of the Working Class in Russia" by V. V. Bervi (N. Flerovsky). Preparation for mass "H. in N." began in the fall of 1873: the formation of circles intensified, among which the main role belonged to Tchaikovites, the publication of propaganda literature was being established (printing houses of the Tchaikovites in Switzerland, I.N. Myshkina in Moscow), peasant clothes were procured, in specially arranged workshops, young people mastered crafts. Began in the spring of 1874, the mass "ch. In n." was a spontaneous phenomenon that did not have a single plan, program, organization. Among the participants were both supporters of P.L. Lavrov, who advocated the gradual preparation of the peasant revolution through socialist propaganda, and supporters of M.A. Bakunin, striving for an immediate revolt. The democratic intelligentsia also took part in the movement, trying to get closer to the people and serve them with their knowledge. Practical activity "among the people" erased the differences between directions, in fact, all participants carried out "flying propaganda" of socialism, roaming the villages. The only attempt to raise a peasant uprising - "Chigirin conspiracy" (1877).

The movement that began in the central provinces of Russia (Moscow, Tver, Kaluga, Tula) soon spread to the Volga region (Yaroslavl, Samara, Nizhny Novgorod, Saratov and other provinces) and Ukraine (Kiev, Kharkov, Kherson, Chernigov provinces). According to official data, the propaganda covered 37 provinces of European Russia. The main centers were: the Potapovo estate of the Yaroslavl province (A.I. Ivanchin-Pisarev, ON. Morozov), Penza (D.M. Rogachev), Saratov (P.I. Voinaralsky), Odessa (F.V. Volkhovsky, brothers Zhebunev), "Kiev Commune" (V.K. Debogoriy-Mokrievich, E. K. Breshko-Breshkovskaya) and others. In "Kh. in n." O.V. Aptekman, M. D. Muravsky, YES. Clemenz, S. F. Kovalik, M. F. Frolenko, CM. Kravchinsky and many others. By the end of 1874 most of the propagandists were arrested, but the movement continued in 1875. In the second half of the 1870s. "H. in n." took the form of "settlements" organized "By the land and by the will", the "flying" propaganda was replaced by "sedentary propaganda" (the organization of settlements "among the people"). From 1873 to March 1879, 2,564 people were involved in an inquiry in the case of revolutionary propaganda, the main participants in the movement were convicted on the "193-x process"."H. in n." was defeated primarily because it relied on a utopian idea populism about the possibility of the victory of the peasant revolution in Russia. "H. in n." did not have a leading center, most of the propagandists did not possess conspiracy skills, which allowed the government to crush the movement relatively quickly. "H. in n." was a turning point in the history of revolutionary populism. His experience paved the way for a departure from Bakunism, accelerated the process of maturation of the idea of the need for a political struggle against the autocracy, the creation of a centralized, conspiratorial organization of revolutionaries.